[Hong Kong]

Technically, the name “Hong Kong” means “Fragrant Harbor” in Chinese.

Flag of Hong Kong

- Features a white, five petal Hong Kong orchid tree flower in the centre of a red field.

- It’s design was adopted on 4th April, 1990.

- Red is a festive color of the Chinese people.

Currency

- Hong Kong dollar or HKD is the official currency with low taxes and good trading economy because of its geographic location and easily accessible labor.

Climate

- Hot and humid for much of the year, it is hardly surprising that some early British colonists wondered why their government ever took Hong Kong Island in the first place.

Geography

- It is made up of 4 parts- Hong Kong Island, Kowloon Peninsula, the New Territories, and the outlying islands.

- Kowloon is a flourishing part where Tsim Sha Tsui, Yau Ma Tei and Mong Kok are most popular destinations.

- Over time, Hong Kong would become a booming port and thriving metropolis.

Country or City?

- Hong Kong, officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong SAR), is an autonomous territory on the eastern side of the Pearl River estuary in South China.

- Hong Kong is the fourth-most densely populated region in the world with about 7 million people living in the area.

- Hong Kong was controlled by China since the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and became a British colony in 1842. On 1st July, 1997, HK was reunited with China. Today, it has many difference from mainland China such as having different economic systems as well as political systems making it almost an independent “country” by itself and maintains a separate political and economic system apart from mainland China.

- Mainland China and Hong Kong have separate governments, schools, languages and political parties. One country, two systems. But is it? Look Here.

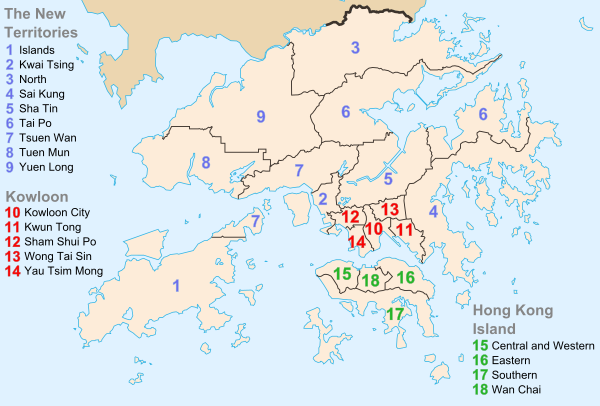

Administrative Divisions

- The territory is administratively divided into 18 districts.

Languages used in Hong Kong

- Cantonese, English, Putonghua and other Chinese dialect speakers.

First Opium War

See these videos once you reach the “First Opium War*” bold text in the Hong Kong in History/Hong Kong in detail section.

- Part 1: Trade Deficits and the Macartney Embassy

- Part 2: The Righteous Minister

- Part 3: Gunboat Diplomacy

- Part 4: Conflagration and Surrender

Hong Kong in History/Hong Kong in detail

- On January 25, 1841, a British naval party landed and raised the British flag on the northern shore of Hong Kong, which was a small island located in the Pearl River Delta in southern China. The next day, the commander of the British expeditionary force took formal possession of the island in the name of the British Crown.

- The British occupation would last until midnight on July 1, 1997, whereupon Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. As newspapers throughout China proudly declared, Hong Kong was “home at last”.

- Until recently, however, historians paid little attention to Hong Kong and scholars of British colonialism concentrated mainly on Africa and India.

- Hong Kong was arguably the most important place in China for more than 150 years, however, precisely because it was not politically part of China and has been China’s most critical link to the rest of the world. More recently, it has attained worldwide acclaim for its innovative cinema.

- It was of particular use to the Chinese during the Korean War, 1950-1953, [ was a war between North Korea (with the support of China and Soviet Union) and South Korea(with the support of the United States) ] as scarce goods such as gas, kerosene, and penicillin were smuggled in during the American and United States official trade ban.

- There is this popular saying, “When there’s trouble in Hong Kong, go to China; when there’s trouble in China, go back to Hong Kong.” For most of the Hong Kong’s colonial history, however, the trouble was almost always in China, which meant that Hong Kong was often at the receiving end of a massive wave of immigrants from China. Hong Kong was depended on these immigrants for their labor and capital.

- Colonialism transformed Hong Kong’s historical development, shaped the form of the encounters between the Chinese and British, and determined power relations between them.

- Especially in the mid-1800s, Hong Kong was tightly connected to India- through trade, primarily cotton and opium, and by a regular passenger ship service between the two colonies.

- It’s reputation as a free port with low taxes and minimal government intervention in its economy has also drawn the praise of the free- market economists such as Milton Friedman

- British sources generally dismissed idea of Hong Kong as having any real history until the British arrived. A guidebook written in 1893 by a local British resident insisted that until 1841 Hong Kong “existed only as a plutonic island for uninviting sterility, apparently capable only of supporting the lower form of organisms.” Open to interpretation but precolonial Kong was not the “barren island” that British historians, colonial officials have often described. Archaeological findings from the Hong Kong region date back almost six thousand years.

- The rise of the British presence in China, which led to the colonization of Hong Kong, is part of the longer story of European expansion that began in the late 1400s and lasted until after WW1. Merchants came to China from Europe during the Tang(618-907) and Yuan dynasties via the Silk Road, the overland trade routes connecting the northwest frontiers of China with the Middle East. Many Europeans visited China to trade , some even working for the Yuan government. After the collapse of the Yuan in the mid-1300s, however, China had little contact with Europe. Now, the Ming government (Ming ruling dynasty , 1368-1644) allowed the Portuguese in 1557 to establish a permanent settlement at Macau, a small peninsula to the southwest of Hong Kong. Although the Qing (was the last imperial dynasty that ruled China from 1644-1912, which was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China) banned overseas trade, Macau soon became the center of a “hemispheric exchange of commodities.” Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and porcelain made their way from Macau to Europe. Macau also became a base for the introduction of Christianity and western learning to China, through the efforts of European missionaries.

- As British ships eventually made their way to Chinese waters, in 1654 the Portuguese allowed the British East India Company to land in Macau. After the Qing ban on overseas trade was lifted in 1684, British merchants used Macau as their headquarters to trade in the harbor at Huangpu.

- Under what became known as the Canton System, or the Cohong System, China’s international trade was conducted through a group of Chinese hongs, or merchant houses, especially authorized and licensed by the Qing government. The word “cohong” comes from gonghang, meaning “officially authorized firms.” Western merchants trade in Canton, confined to factories, or manufactories, rented from the Chinese hongs (from October-March). During the off-season, from April to September, the merchants returned to trade in Macau. Although the foreigners frequently complained about the restrictions and conditions in Canton, these inconveniences were minor compared to the fortunes that could be made in silk, tea, and later, opium.

- Standard argument goes like- Britain took Hong Kong not to obtain more territory but rather to promote and protect its commercial interests in China. It was occupied not with a view of colonization, but for diplomatic, commercial and military purposes. Since the Chinese were thought to be unable to provide these conditions, the British had to provide them.

- After British first occupied Hong Kong in 1839 during the First Opium War* with China (Yes, now you can go through the Opium war series), few British officials considered seriously the idea of Hong Kong as a permanent colony (it would not formally become a colony until June 26, 1843).

- Even after the British took formal control of Hong Kong in 1841 under the short-lived Convention of Chuenpi (which both sides considered so unsatisfactory that some scholars wonder if the treaty was even signed), British officials held differing and often conflicting views about Hong Kong’s potential.

- Charles Elliot, British superintendent of trade in China and first administrator of colonial Hong Kong, was convinced that Hong Kong would be the perfect base for British commercial, military, and political operations in China.

- Robert Fortune, an English botanist and adventurer who visited Hong Kong in 1843 and 1845, summarized the virtues of Hong Kong’s harbor: “Hong-kong bay is one of the finest which I have ever seen: it is eight or ten miles in length, and irregular in breadth; in some places two, and in other six miles wide, having excellent anchorage all over it, and perfectly free from hidden dangers. It is completely sheltered by the mountains of Hong-kong on the south, and by those of the main land of China on the opposite shore; land-locked, in fact, on all sides; so that the shipping can ride out the heaviest gales with perfect safety.”

- Britain acquired Hong Kong during the First Opium War (1839–1842). By the late 1700s, the volume of trade between China and Britain was tilted in China’s favor; the British had little more than silver to offer the Chinese for their silk and tea. The British responded by importing opium, grown and prepared in British India. Although opium had been introduced to China by Arab traders almost one thousand years earlier and was also cultivated in southern China, it was used primarily for medicinal purposes. By the 1700s, however, it was being smoked mainly as a narcotic. When the Qing reaffirmed its ban on importing opium in 1796, the EIC responded by selling its opium to country traders—British, Indian, Parsee, and Armenian traders—who then imported the drug to China in small, private “country ships.” Although importing opium was prohibited again by Qing imperial edict in 1800, the trade thrived.

- As the demand for opium increased, British merchants became frustrated with both the constraints of the Canton System and the Qing ban on opium. When the EIC’s monopoly over British trade with China ended in 1834, the British government dispatched Lord Napier to supervise British trade with China. Whereas the EIC traders had dealt with the superintendent of the Guangdong maritime customs, Napier was determined to deal directly with Qing officials as diplomatic equals. Instead, Napier was held hostage in the Canton factories until he agreed to leave China, an incident that might have led to confrontation between Britain and China had Napier not died shortly after from malaria. Because taxes were paid in silver, the outflow of silver used to pay for opium had the potential to create a vicious cycle of weakened livelihoods, decreased state revenues, and domestic unrest. Acknowledging Britain as a diplomatic equal would tarnish the Qing emperor’s reputation as the Son of Heaven, not just in China but throughout Asia. As the number of Chinese opium addicts soared, already scarce land was being wasted on poppy cultivation. How could the emperor allow this trade to continue without jeopardizing his moral claims to the throne and to being “the mother and father of the people”? Some Qing officials argued that the worst of the problems (including the corruption encouraged by the high price of opium as contraband) could be ended by legalizing the opium trade, but in 1838 the Daoguang emperor decreed that the trade in this “foreign mud” must end.

- Many British officials agreed that the Qing government had every right to prohibit the opium trade. But some Europeans were convinced that the Chinese themselves had caused the demand for opium. An early European historian of Hong Kong later insisted how “the taste for opium” was “a congenital disease of the Chinese race.” The opium trade had been tolerated for so long, and the Qing government simply appeared too weak to restrict it. Opium was imported and sold, while the ‘oozing out of fine silver’ went on as usual.

- However, in March 1839 Lin Zexu, an official recently appointed by the Qing to end the opium trade, launched an antiopium campaign in Guangdong province. Lin subsequently took hostage some 350 foreigners—among them British Superintendent of Trade Charles Elliot—in Canton and confiscated their opium stocks.

- The First Opium War ended officially with the Treaty of Nanking, signed on August 29, 1842. Apart from imposing on China a huge indemnity, ending the cohong monopoly, fixing rates for customs duties, and opening five Chinese ports to foreign trade and residence, this treaty ceded the island of Hong Kong to Britain “in perpetuity.” It also granted the British the right of “extraterritoriality” (meaning that British subjects in China would be tried by British judges), and the “most-favored-nation” clause guaranteed that Britain would receive the same concessions subsequently granted to any other nation. This treaty is known in China as the first of the many so-called unequal treaties forced on a weak China after military defeats by Western powers in the nineteenth century.

- The military victory that gave the British the upper hand in the Treaty of Nanking was made possible not just by British military superiority but also by Chinese collaborators. The British received help from the Chinese before and during the First Opium War and in the building of their new colony. Even though authorities in Canton ordered the Chinese in Hong Kong to resist the “barbarians,” the British encountered practically no resistance when they first occupied Hong Kong Island. A British military surgeon wrote that the inhabitants of Hong Kong “appear to be industrious and obliging…. From all accounts they seem in general to have been very peaceably disposed; nor did they exhibit any marked approbation or disapprobation, on their transfer to the British sway.”

- When the British took control of Hong Kong in January 1841, the northern shore of the island was for the most part unoccupied, and the rest of the island consisted mainly of small farming and fishing villages. By early 1842, Hong Kong was a bustling town with between fifteen thousand and twenty thousand inhabitants, complete with official buildings such as a magistrate’s office, post office, land and record office, and jail.

- One reason that Hong Kong was unable to attract large Chinese merchants was that Chinese authorities in Canton used various restrictions to discourage wealthy Chinese traders from coming to the colony. Some colonial officials were convinced that Chinese authorities in Guangdong deliberately deported vagabonds, vagrants, and thieves to Hong Kong, both as a way to get rid of criminals and to undermine the stability of the colony.

VisualPolitik Links

- Why is Hong Kong in decline?

- Why does Hong Kong have world’s most expensive homes?

- Will China succeed in subjugating Hong Kong?

Am I confused ?

Please, stop it.